Alternate row spraying is an application method where the air-assist sprayer does not pass down every alley during an application. The sprayer operator is relying on the spray to pass through one or more rows and provide acceptable coverage to the entire canopy (or canopies) on a single pass.

Some state agencies promote this spraying strategy to various degrees, and many sprayer operators (whether they admit it or not) have used this method of spraying. I have advised it myself for very young and/or very sparse vineyard and orchard plantings, but never without confirming coverage. When I tell operators that I have serious reservations about alternate row spraying, they defend it. Here are the most common justifications I’ve heard over the years, and my response:

| Justification | Reply |

| “I do not have enough spray capacity to spray every row when time is short.” | You need more sprayer capacity. Get another sprayer so you can get spray on in time or invest in a multi-row sprayer is possible. |

| “ARM spraying saves money and reduces environmental impact because I use less pesticide.” | Technically, if you travel every second row with a sprayer calibrated to travel every row, you have indiscriminately reduced your carrier and chemical inputs by half (or more). Without close monitoring you may compromise your efficacy. |

| “I only perform ARM spraying early in the season when canopies are empty, or only on young plantings.” | I grudgingly grant this one as long as coverage is closely monitored. I’ve prescribed it myself in young or sparse plantings where I couldn’t get the sprayer output low enough to prevent drenching the targets. |

| “The spray plume in the alley beyond the target row must mean the spray is providing adequate coverage. More is better!” | If the spray is blowing through the canopy, it isn’t landing in the canopy. Further, if the air speed/volume is too high, droplets can ‘slipstream’ past the target without impinging on them. I’ve removed water-sensitive paper from canopies with barely any spray on them despite the plume in the downwind alleys. It looks like a magic trick, albeit an unhappy one. |

| “Uncooperative weather doesn’t always leave me enough time to spray the entire crop, and it is the lesser of two evils to spray alternate rows than not at all. I’ll make sure I come back to spray the other rows later.” | Choosing to do half a job requires an understanding of the products’ mode of action. If you are spraying an insect at a particular stage of development, there’s no “coming back later” to get that generation – if you missed, your window has closed. If it’s a protective fungicide that offers no kick-back, then once the disease has infected tissue, the damage is done. Get the spray on as best you can, but if it washes away before it has a chance to dry sufficiently, be prepared to reapply at the earliest opportunity as long as the label allows it. |

| “ARM has always worked in the past.” | Would you mind picking my lotto numbers for me? You’re a very lucky person! |

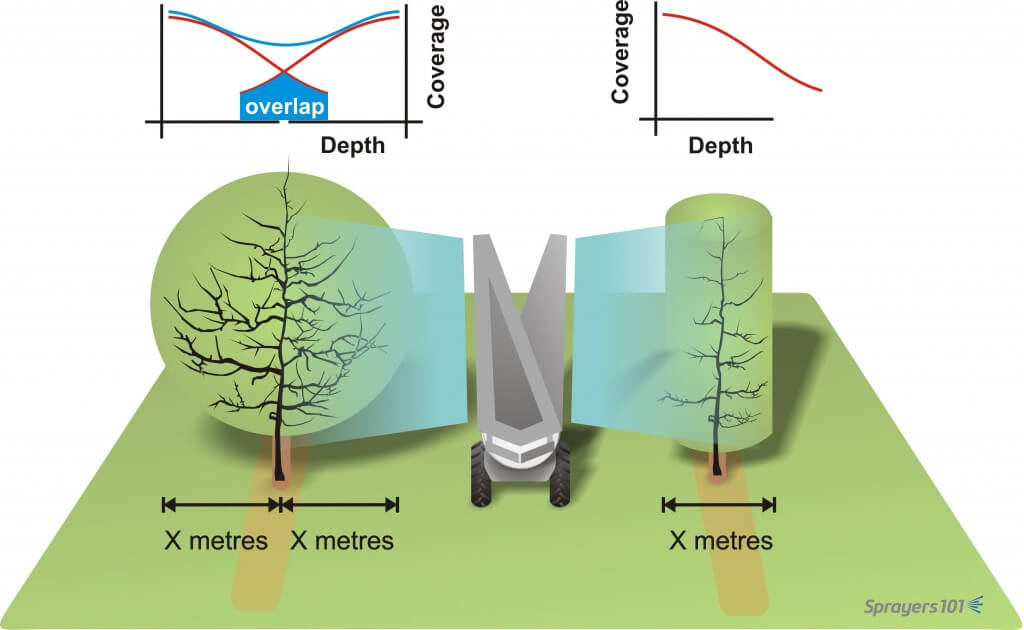

My reservations about ARM spraying come from research that has shown that coverage is almost always compromised when spraying from one side of a canopy. The spray must pass through the canopy to reach the far side, and the canopy filters droplets from the air as it passes through. This reduces the number of droplets available to cover the far side. In addition, high velocity spray will create “shadows” where any targets on the immediate far side of a leaf or branch become shielded and receive little if any coverage. Further still, fine droplets slow quickly as they leave the nozzle and take a long time to settle. As the entraining air slows and becomes erratic, the droplets float and change course, making their behaviour hard to predict.

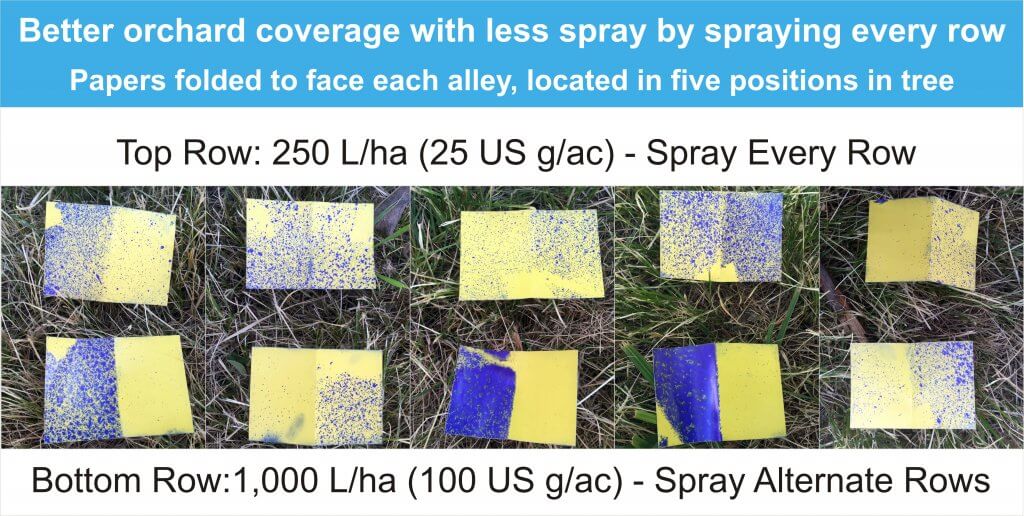

The cumulative impact can be seen in this infographic I built in 2016. The orchardist was a dyed-in-the-wool ARM applicator and he was resistant to driving every row because it took so much time. I wanted to show that he could claw back some of the lost time by spraying less pesticide every row versus his current volume every second row. He would need fewer refills, and save a LOT of unnecessary pesticide. The water sensitive paper does the talking, and while I’d like to think I’ve convinced him, I’ll bet he’s still out there dicing with fate.

A very popular argument in favour of ARM spraying comes from orchardists that are shifting from semi dwarf to high-density plantings. They ask “How it is different to spray a four foot diameter tree from one side compared to an eight foot diameter tree from both sides”?

Well, we know coverage is reduced as a factor of distance. Spraying from one side gives a single opportunity to cover the middle and far side of a canopy, whereas spraying from both sides provides an opportunity for an overlap in coverage. Essentially, the centre of a canopy receives the cumulative benefit of two sprays. Coverage is therefore always improved when spraying from both sides, period.

Why, then, do some sprayer operators claim that alternate row applications work? Because sometimes, they do! Just because coverage is reduced doesn’t mean it isn’t sufficient to protect the crop. It simply means that the potential for poor coverage and reduced dose is dramatically increased by alternate row applications. A sprayer operator might perform alternate applications successfully for years before conditions conspire to defeat the application: unfavourable wind, poor timing, increased pest pressure, poor pruning practices, excessive ground speed, high temperatures, low humidity, insufficient spray volume, and several other factors might occur simultaneously and reduce coverage below a minimal threshold for control. This confluence of bad luck may not happen the first year, or the second, but eventually…

Product failure isn’t the only concern. Repeated reduced dosages may play a role in developing resistance. In those situations where the operator recognizes insufficient coverage, they may have to spray more often to compensate, negating any savings in time or product. Reduced dosage is a common error when a sprayer operator elects to use ARM.

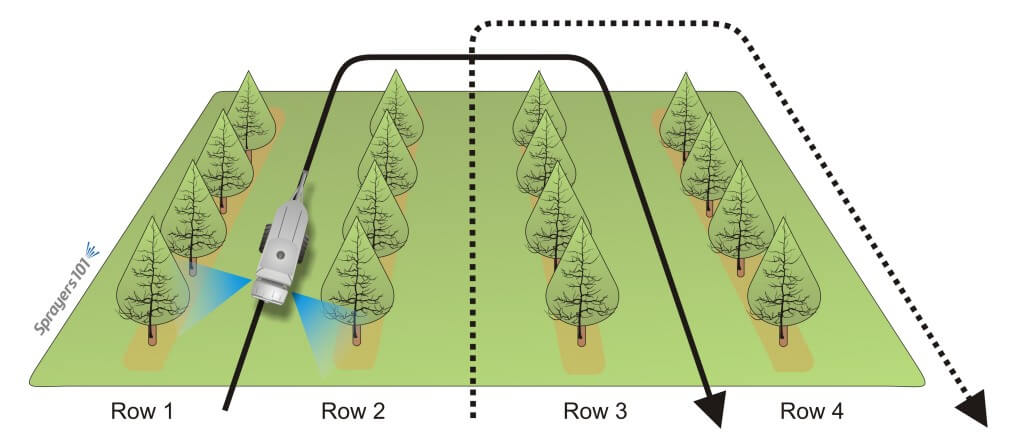

If you still aren’t convinced, at least perform alternate row spraying the “right” way. Here are three situations that I’ve heard operators refer to as alternate row spraying. Situation 1 is most common, but to my mind only Situation 2 would be considered acceptable. Even then, confirming coverage is a must.

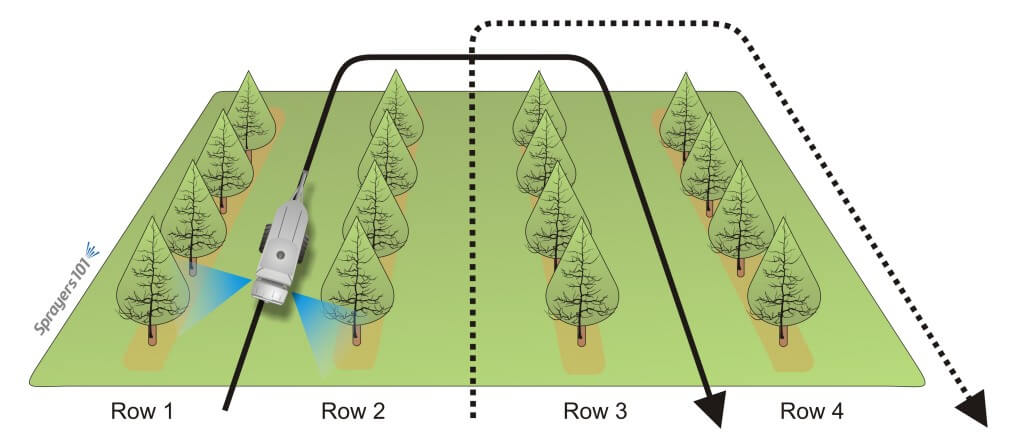

Situation 1:

The sprayer has a typical calibration for spraying every row, but only drives alternate rows. The first application (solid line) covers different rows from the second application (broken line). The operator will claim to spray more frequently, but generally does not perform the second application unless there is high pest pressure. The result is half-a-dose per hectare per application.

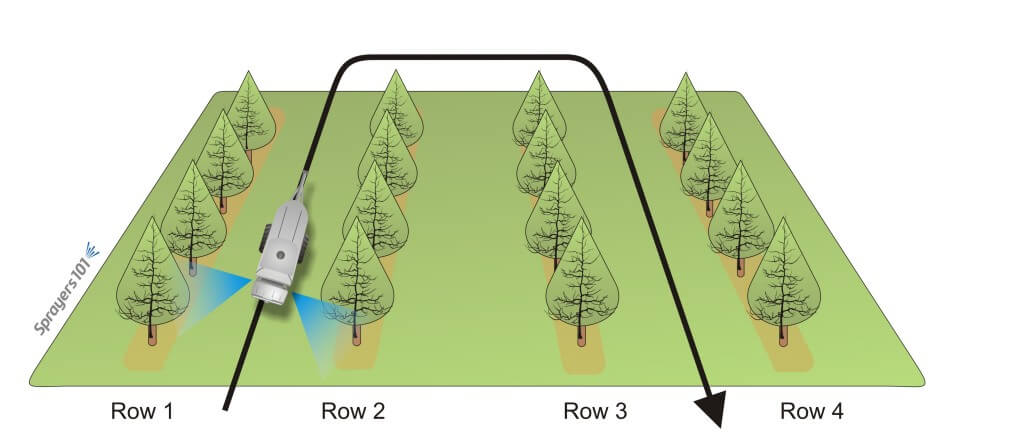

Situation 2:

The sprayer is calibrated for double output compared to a typical every-row situation, and the operator drives alternate rows. The result is that the hectare gets the whole dose per application, but coverage is always inconsistent.

Situation 3:

Since the sprayer will only drive alternate rows, the operator mistakenly sets the sprayer to emit half the output compared to a typical every-row situation. The first application (solid line) covers different rows from the second application (broken line). The result is a quarter-dose per application, and if the operator chooses to spray a second time, the hectare will only ever get half-a-dose. Yes, this happens.

So, my final word on alternate row applications is that they should be performed with extreme caution. I’ve used them myself in early season applications in new plantings, but never without confirming coverage with water-sensitive paper, and never in conditions that might further compromise coverage to the point that the application does not give control.

Caveat Emptor!