On a trip to Mildura, Victoria I met Matthew McWilliams, Director at Interlink Sprayers. His passion for innovation was exciting. He described Interlink’s history of near-annual design improvements, each of which made the last generation of sprayers look a bit passé. Continual improvement means spending a lot of time educating and upgrading customer’s sprayers, but that level of support is worth it. Their strategy of drawing from leading international designs and improving on them has led to a unique axial fan assembly that boasts impressive benefits for those spraying large canopies.

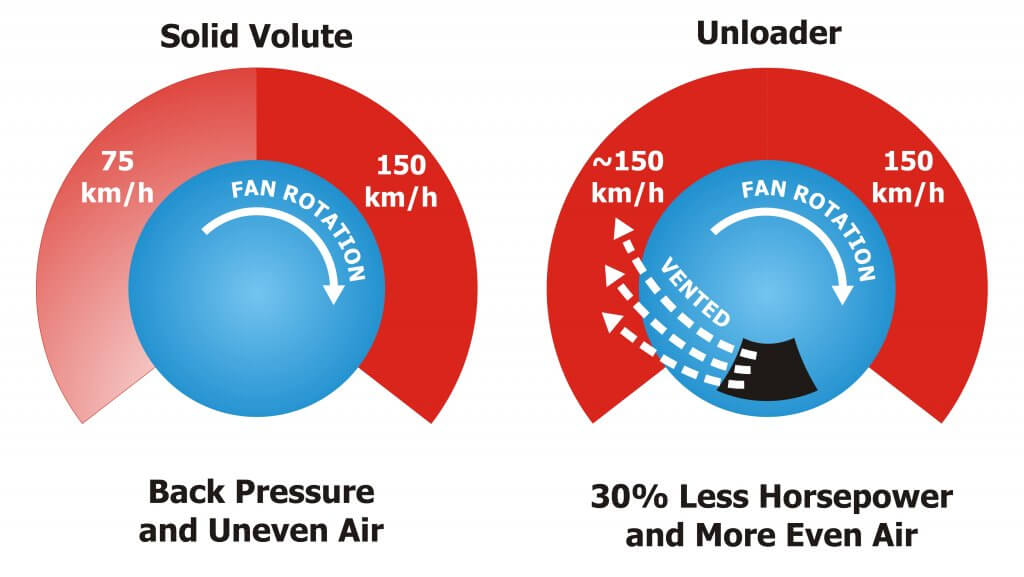

Matt explained a problem common to any axial fan: they hate back-pressure. When an axial fan blows air against a volute, which redirects the air laterally, the back-pressure acts like an air break. It pushes back against the fan, flexing the blades, reducing output volume and reducing efficiency.

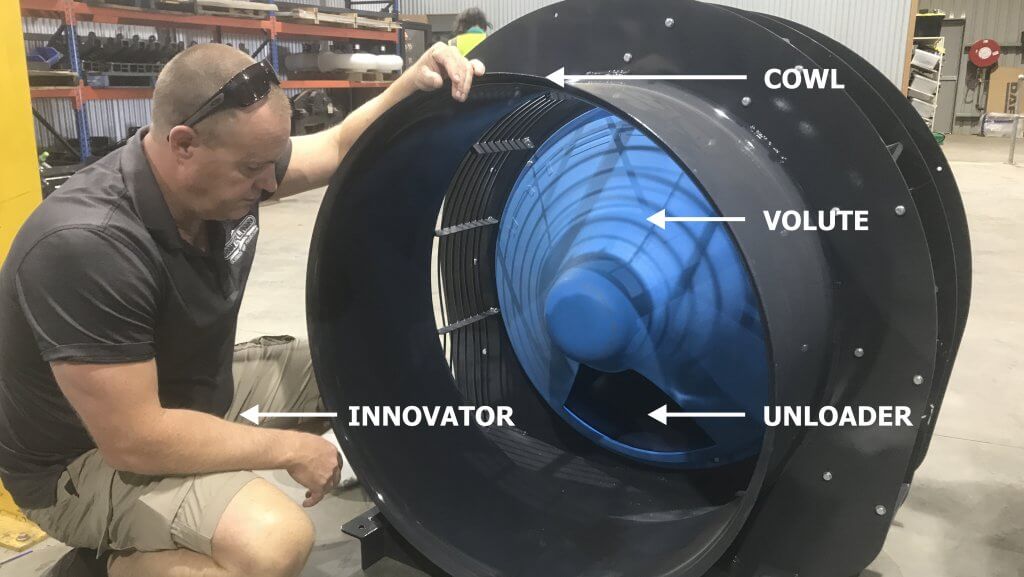

In an effort to relieve some of this pressure, Interlink cut a hole in the volute (called an “Unloader”). Venting reduced the pressure and increased efficiency significantly. It did something else, too, but we’ll get to that later.

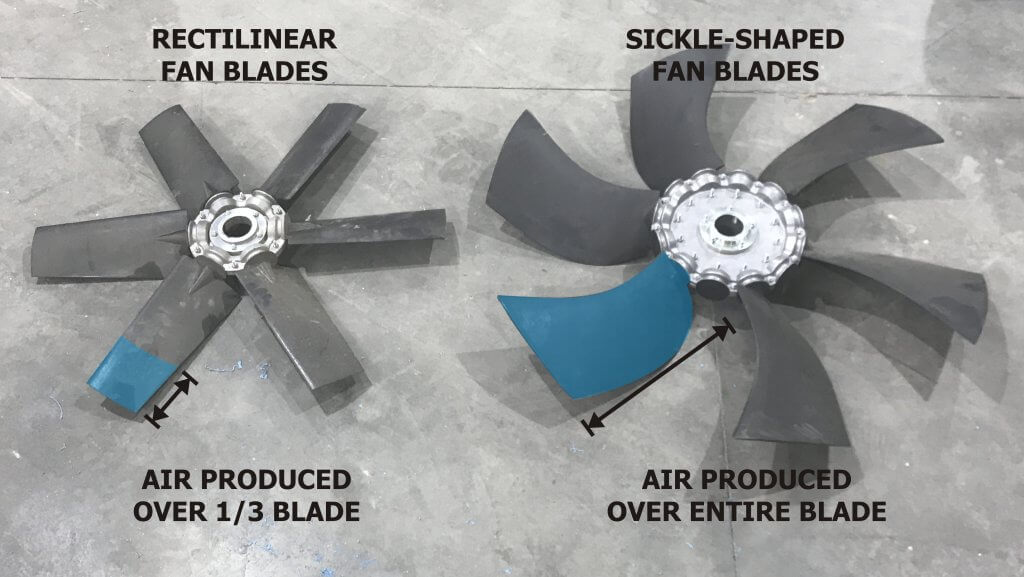

This success led them to reconsider fan blade design. Classic, rectilinear fan blades are inefficient. They only produce air over the last 1/3 of their length. Using computational fluid dynamics, they modelled an efficient sickle-shape that creates pressure over the entire length. This means it can produce as much volume as a rectilinear blade, but with fewer revolutions.

When the new blades were combined with the Unloader, they were able to move the fan closer to the volute and make the cowl longer. A less-exposed fan is not only safer, but its proximity to the volute increased efficiency.

The result was a 2.5x increase in pressure and a concomitant 30% savings in horsepower. In other words, while similarly-sized sprayers were using 25 L (6.5 US gal.) of fuel per hour, they created the same air volume and speed using 17 L (4.5 US gal.) fuel per hour.

But why stop there?

Nut orchards in Australia and the US can grow up to 21 meters (~70 feet). A low-profile axial sprayer must produce a great deal of air volume to both penetrate the canopy and reach the top. Increasing fan diameter can help, but perhaps two fans are better? Air-O-Fan has their twin-fan system, where two shaft-driven fans with reversed blade pitches produce high-volume turbulent air. Interlock decided to try it.

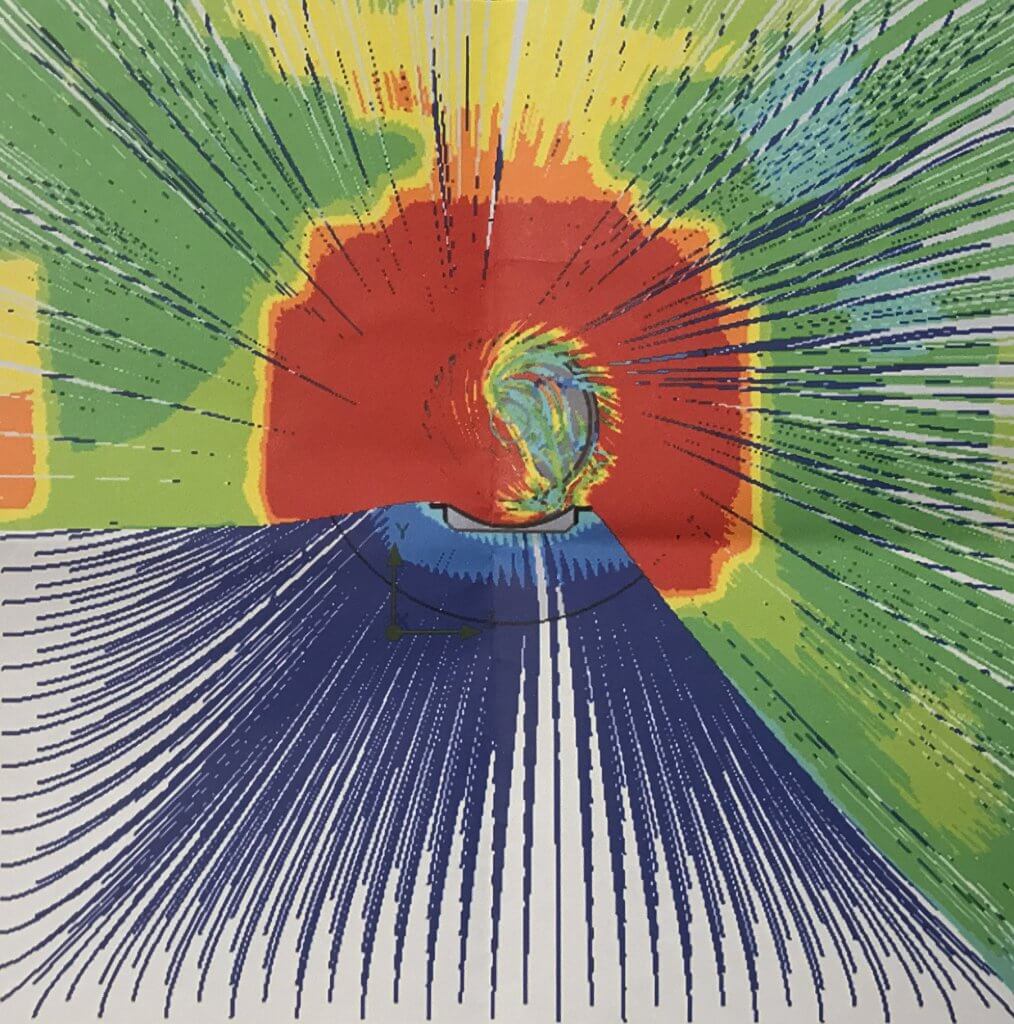

When two hydraulically driven fans were placed back-to-back (spinning counter to one another) the Unloaders did something Unexpected. Normally, an axial fan blowing against a volute creates deflection, causing higher speeds on the downward side of the fan. Most sprayers use vanes to correct this, but they cause back-pressure. Serendipitously, when placed back-to-back, the pressure vented through the Unloaders was reclaimed on the upward side of each fan, equalizing airspeed across the outlet.

And there’s still more. Since this counter-rotation twin fan design is hydraulically driven, it is not restricted by a shaft. This allows the head to be lifted off the ground. Quite often in large orchards, air and nozzles are aimed too low, wasting spray below the canopy. Lifting the fan and nozzle banks brings everything closer to the top of the canopy; a notoriously difficult target to reach. It also reduces the level of dust and detritus stirred up from the canopy floor. Operators reported that the elevated fan head helped keep fan intakes and radiators (required on Australian airblast sprayers) clear of debris.

This low-profile axial airblast fan is a refreshing new approach to a design that has seen only marginal improvement over the last 20 years. Given the pace of innovation in Matt’s factory, I’m sure the next set of improvements will be in place by the time this article is published.