An orchard spraying scenario

Here’s a common situation: An orchardist following IPM identifies a pest that poses an economic threat. It’s an annual pest and spraying is really a matter of when, not if. The operation is 150 acres and runs three airblast sprayers; two have a tower and one does not. Multiple varieties are planted in several blocks on different rootstocks and they are at different stages of maturity. The newer blocks are trellised high density trees and the older blocks are semi-dwarfs on different row spacing. Let’s also imagine the pruning team hasn’t finished yet, so some trees are not pruned.

The orchardist turns to the pesticide label to decide how to spray such variable targets. It prescribes a range of doses per planted area (not canopy size), depending on the pest pressure. It advises the orchardist to use “enough water” to ensure “good coverage” without incurring “runoff”.

The orchardist recognizes that the label is vague, and elects to rely on what has worked historically: A water-soluble pouch is dropped into each tank (dose is close enough), and each sprayer operator is instructed to drive at an efficient speed (get it done because rain is coming), spraying until the tank is empty. They say that if a tank is running low before the job is done, speed up and stretch it. If the spray is overshooting a younger planting, they suggest turning off the top nozzles and/or driving faster.

Airblast operators face this situation regularly. The question is: “Is there a problem with spraying this way if it results in a respectable crop of quality fruit?” Agricultural engineers specializing in application technology in Spain, Australia, Great Britain and the United States say there is a problem, and on behalf of Canada, I completely agree with them.

Canopy and Sprayer Variability

The fundamental problem is inconsistent spray coverage and avoidable waste (of time, water and pesticide) due to variability. Our scenario notes multiple sprayer operators, different models of sprayer, and a range of varieties, orchard architectures and canopy management practices. The label does not allow for any of these factors, adhering to a rate based on planted area and remaining silent on water volume.

International peer-reviewed journal articles stretching back to the sixties have conclusively demonstrated order-of-magnitude differences in the area-density of orchard canopies from one acre to the next. There can even be fold-differences in canopy area-density in the same planting as the season progresses. A label prescribing a fixed dose based on the area planted is not appropriate for any vine, bush, cane or tree crop, and the result is that more crops are over- or under-sprayed than receive appropriate coverage.

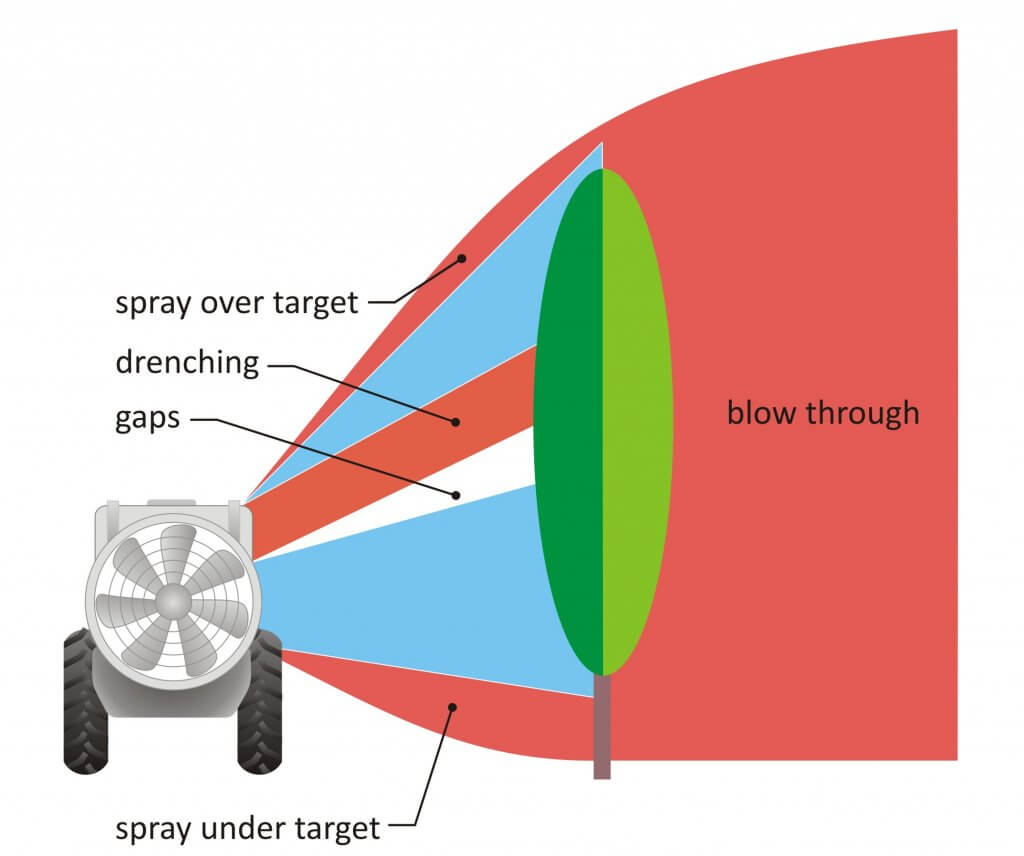

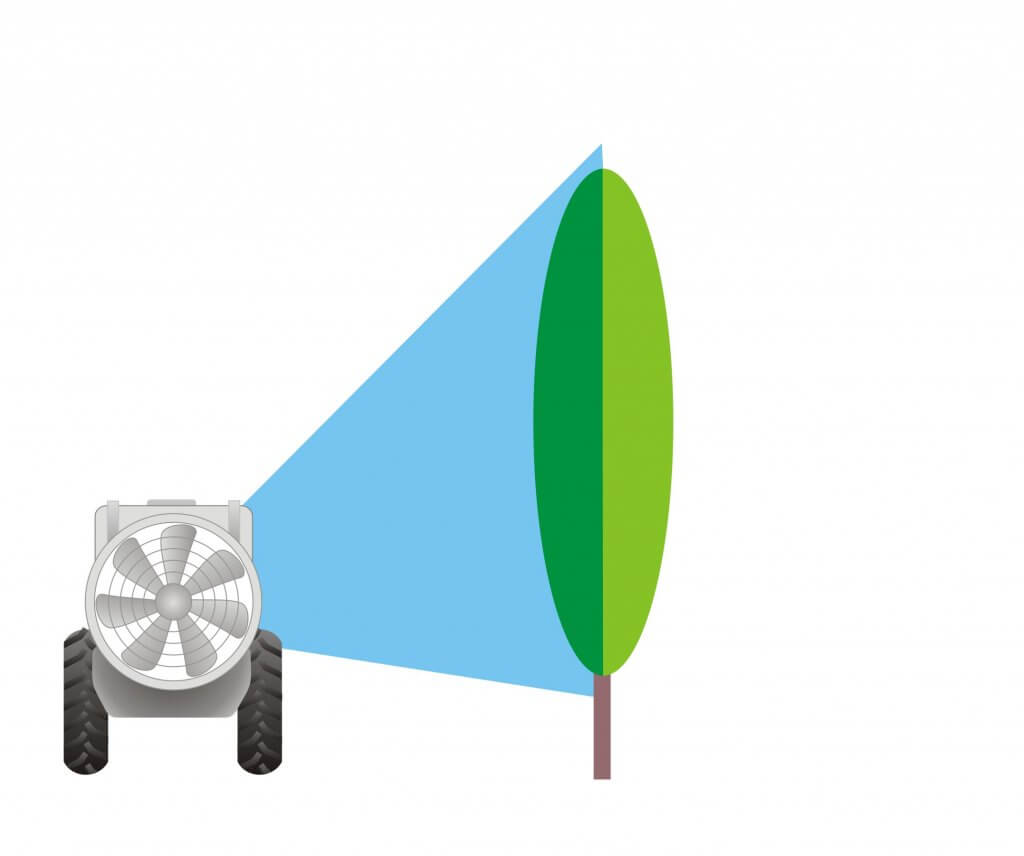

Let us not forget the variability that comes from a poorly adjusted sprayer. I won’t to attempt to quantify the impact (although some researchers have suggested order-of-magnitude differences from sprayer to sprayer). Instead, let’s illustrate it as a conceptual “before and after”:

Beyond the immediate impact on efficiency, variability makes it difficult to diagnose pesticide effectiveness. As an example, there was a scab outbreak in Ontario in 2009 that elicited questions about timing, weather, product choice and resistance. There was very little attention given to spray coverage, which to my mind should have been the first question if only to eliminate it as a potential culprit. This is because each operation interprets labels differently, and very few confirm coverage in any quantifiable way. This practice makes it more difficult to identify a cause when crop protection fails.

Optimizing pesticide rates

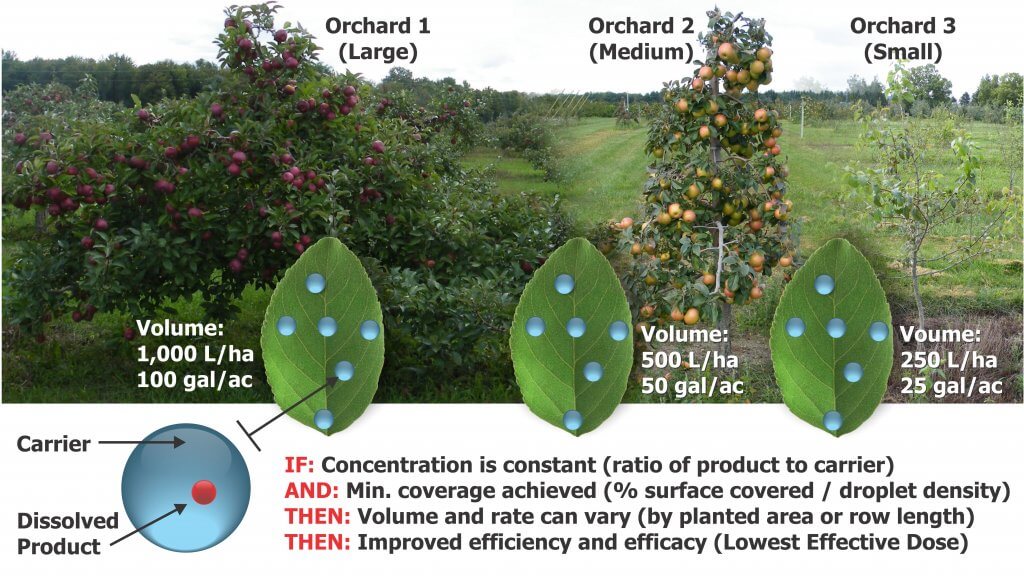

That was a lot of preamble to describe an issue that many orchardists are already aware of. What is needed is a way to adjust the amount of pesticide per unit ground area (i.e. the label’s prescription) to achieve consistent foliar coverage for canopies of varying shape and density. The concept is visualized in the following figure. In addition, the method has to be simple, intuitive and effective.

Many models have been proposed to tackle the dose expression issue, including Tree-Row Volume, Leaf Area Index, Leaf Wall Area, PACE+ and DOSAVIÑA. There are advantages and disadvantages to each method. Standing on the shoulders of giants, we combined aspects of each of these models, including incorporating coverage factor research from USDA ARS work in nurseries, to develop the Crop-Adapted Spraying (CAS) method. It is neither complicated nor sophisticated. It formalizes a series of qualitative calibration techniques and the objective is to achieve a target foliar coverage pattern. When achieved with sufficient accuracy, pesticide efficacy is maintained and waste is greatly reduced.

Caveats

Perhaps I shouldn’t point out flaws before I describe the model’s effectiveness, but it’s important to understand that CAS relies on a few critical assumptions.

The first assumption is that the sprayer operator’s typical ratio of formulated product to carrier is appropriate. We need a starting point for adjusting the amount of pesticide per unit planted area, and unless the label specifies a concentration (i.e. a ratio of formulated product to water) or a minimum amount of product per planted area, this is a reasonable starting point. The appropriateness of this assumption is evidenced by a history of satisfactory pest control in the orchard.

The second assumption lies in defining a threshold for sufficient coverage, and this is a real challenge. Applications can be concentrate or dilute. Some products translocate in the leaf or redistribute on the leaf surface while others do not. Even the droplet size employed (e.g. A mist blower’s fines compared to Medium-Coarse droplets produced by an air induction nozzle) will affect dose, bioavailability and how long residues are active. So, how does one draw a universal line in the sand and say “this much is enough”?

Our threshold for suitable foliar coverage has evolved through experience, literature review and independent experimentation in several countries and in multiple 3D cropping systems. We propose 10-15 % surface coverage and a minimum of 85 droplets per cm2 on a minimum 80% of the canopy. This standard is intended to be practical, versatile and robust in order to safely represent sufficient coverage for most foliar insecticides and fungicides. It is not suitable for ultra-low volume sprayers (e.g. misters, foggers, air-shear), nor is it intended to be a rigorous, scientific absolute.

For example, a drench application, such as streptomycin or dormant oils, will obviously require more coverage. Plant growth regulators like thinners, stop-drops and foliar nutrients have their own unique criteria. Products that work through vapour redistribution (e.g. some forms of sulfur) and bio-rational products have a minimal dose threshold that must be ensured per planted area, no matter the water volume used. In these cases, Crop-Adapted Spraying may not be appropriate.

So while it is the nature of models that they may not hold in every situation, this threshold has proved successful in multiple Ontario apple (later in this article) and highbush blueberry operations.

The method

The method is a simple and iterative approach that allows growers to adjust the product rate and sprayer output in relation to canopy and sprayer effects on deposits. Follow these steps to adjust the sprayer and optimize coverage. Only do so in conditions you would normally spray in.

Step 1

The sprayer should receive all seasonal maintenance prior to first use and undergo a visual inspection before each spray day.

Step 2

Park the sprayer in an alley between rows of trees and tie 25 cm (10 in) lengths of ribbon along the air outlet. That would be the deflectors on a low profile axial sprayer, the hubs of multifan systems or the ducted outlets on towers. Turn on the air and extrapolate where the air is aimed. Adjust the air to just overshoot the top of the canopy.

Step 3

It is important that the spray slightly overshoot the canopy height. It is less important to spray the lowest point of the canopy as secondary deposition tends to provide sufficient coverage. This may change if fruit weighs down the branches. Ensuring a full swath, turn off any nozzles that are not required. For small and medium canopy sizes, consider using air-induction hollow cones in the top positions of each boom to reduce drift. You may have to increase the rate in those positions to compensate for the fact that nozzles producing larger droplets produce fewer droplets.

Step 4

Affix 25 cm (10 in) ribbons to the upwind and far side of one or more trees. At minimum, affix them at the treetop and along the widest portion of the canopy. With the tank half-full of water, drive past in the spraying gear at the ideal RPMs with the air on. A partner in the next alley should see the highest ribbon move. Ideally the other ribbons will waft as well, but in large, dense canopies they may not. In this case, ensure leaves are moving beyond the trunk. No ribbons should strain straight-out.

This will determine if more/less air is required from the airblast sprayer. The operator can change fan speed (e.g. fan gear), or adjust the sprayer’s travel speed. Lower speed causes air to go higher and deeper and vice versa. In some cases, operators can reduce fan speed by reducing the tractor PTO revolutions by gearing up and throttling down. When air is corrected, determine ground speed in the orchard using smartphone GPS app or a calibration formula.

Step 5

Place and interpret water-sensitive papers per this article. If coverage is excessive, reduce output in corresponding nozzle positions (by replacing them with lower rate nozzles). If you see less than ideal coverage, increase the nozzle rates in those positions.

Be aware that excessive coverage may be unavoidable in the outer edge of the canopy, given that spray must pass through to get to the centre. It is not unusual to see half the deposition mid-canopy when the outside is saturated. Also be aware that ambient wind speed and humidity have significant impacts on coverage. Therefore, only test coverage in conditions similar to your typical spraying conditions.

Step 6

When the canopy grows and fills in sufficiently (usually after petal fall), you may have to reassess coverage to reflect a larger, denser canopy with more surface area. Given the critical nature of early season fungicide applications, it may be preferable to have slightly excessive coverage early season and allowing it to self-correct as the season proceeds. If you are suspicious that the spray is being stretched too thin or you are unsatisfied with the coverage, increase the output.

For high density trees, there may be no need to increase output mid-season. Early in the season, wind travels relatively unimpeded in a high-density orchard and will blow spray off course, reducing coverage and requiring higher water volumes or possibly more air to compensate. As the trees fill in, the average wind speed is reduced and more spray can impact on the target.

Mixing and Work Rate

When the correct sprayer settings and volumes have been determined, the operator will mix their spray tank as they would for their typical application. The sprayer will likely cover more orchard than it has in the past, and the operator will have to re-assess how many tanks are required pre and post petal-fall. If your sprayer is employs conventional hydraulic nozzles (that is, it is not a low-volume sprayer), it is not advisable to go below 400 L/ha (~40 gpa).

This is where OrchardMAX (the free CAS calculator app) can help the operator ballpark the correct rates for each nozzle position and estimate work rate, tanks required, and any potential savings in product.

Apple Orchard Case Study

Three Ontario apple orchards (and one Nova Scotia orchard) agreed to test the model. A block of trees was randomly selected from each operation to serve as the treatment condition. These trees received spray according to the CAS model. The rest of the orchard was sprayed according to the grower’s traditional methods. The orchards included several varieties and represented both semi-dwarf and high density plantings.

| Orchard | Typical spray volume (Control) | CAS spray volume (Treatment) | % Savings | Varieties (age) | Orchard Structure | Years in study |

| Orchard 1 | 486 L/ha | 373 L/ha | 23% | Gala + g. Del (~10 yr old) | High density | 3 |

| Orchard 2 | 748 L/ha | 478 L/ha & 608 L/ha = 543 L/ha | 28% | Macs + Empires (~30 yr old) | Semi-dwarf | 3+ |

| Orchard 3 | 577 L/ha (660 L/ha) | 407 L/ha | 39% (38%) | Gala + Fuji (~20 yr old) | High density | 2 |

| Nova Scotia | 544 L/ha | 416 L/ha | 33% | Jonogold (~10 yr old) | High density | 1+ |

According to the model, each grower sprayed anywhere from 20-35% less per hectare in the CAS block than in their traditionally-sprayed block. In many cases, the overall canopy coverage was improved in the CAS block compared to the traditional method simply by aiming formally wasted spray into the canopy, and reducing volume in those areas that were unnecessarily drenched.

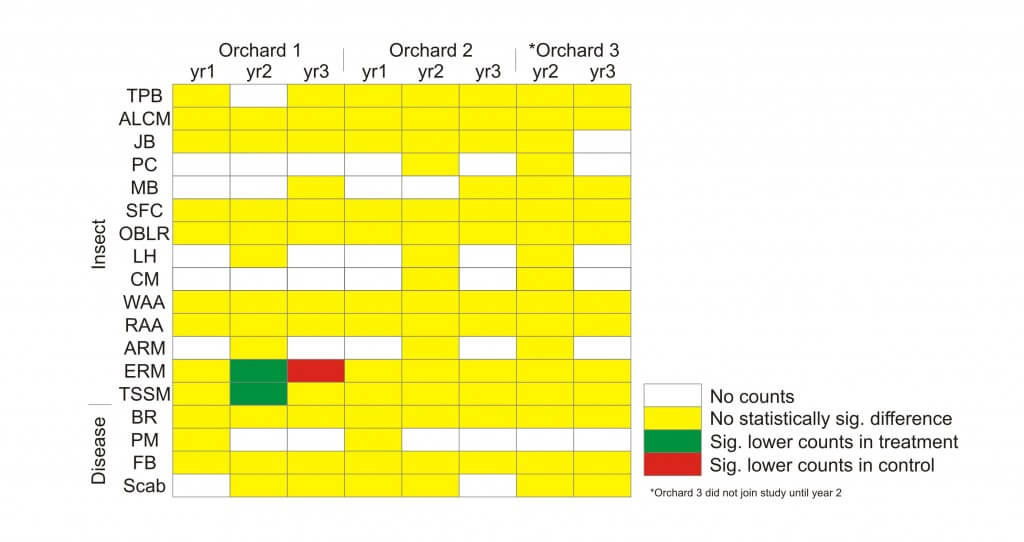

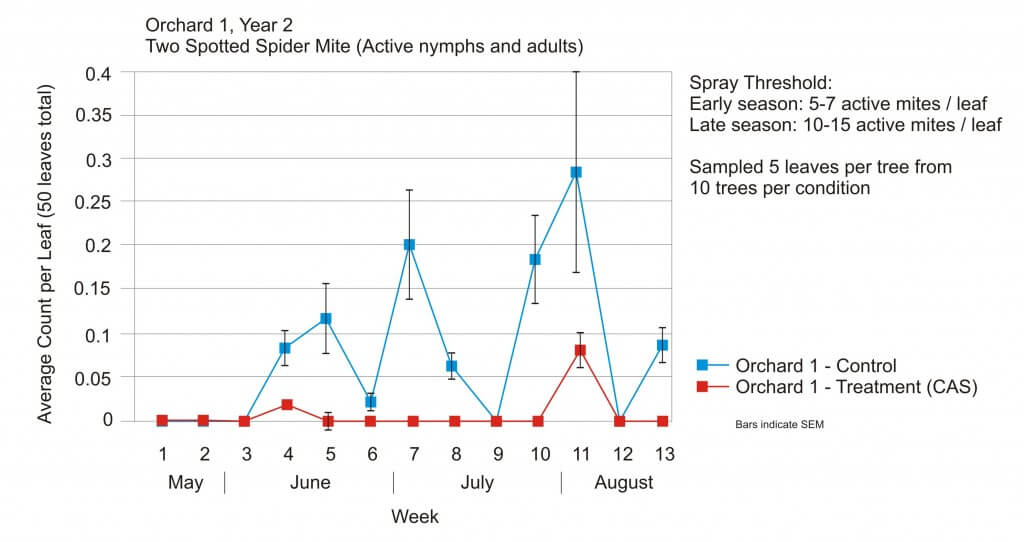

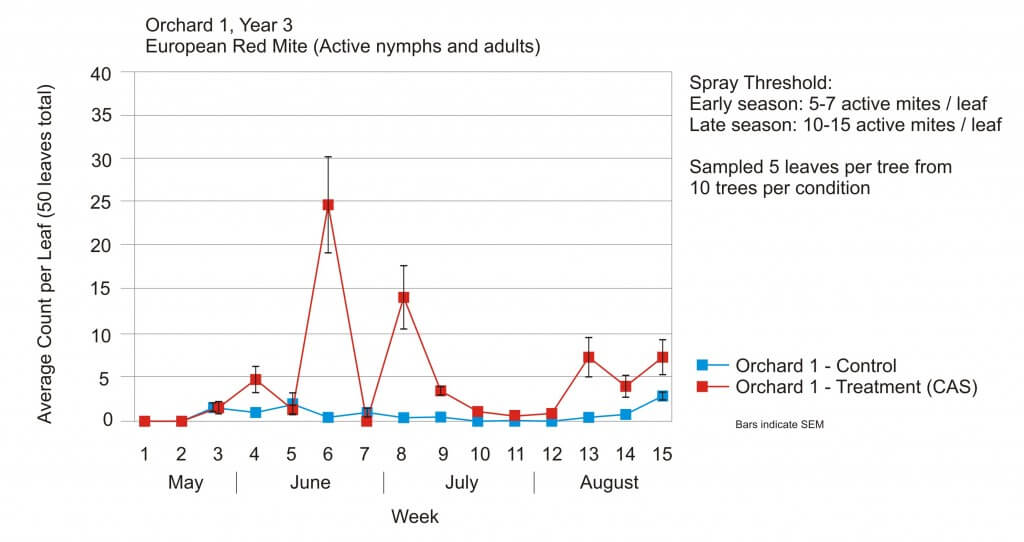

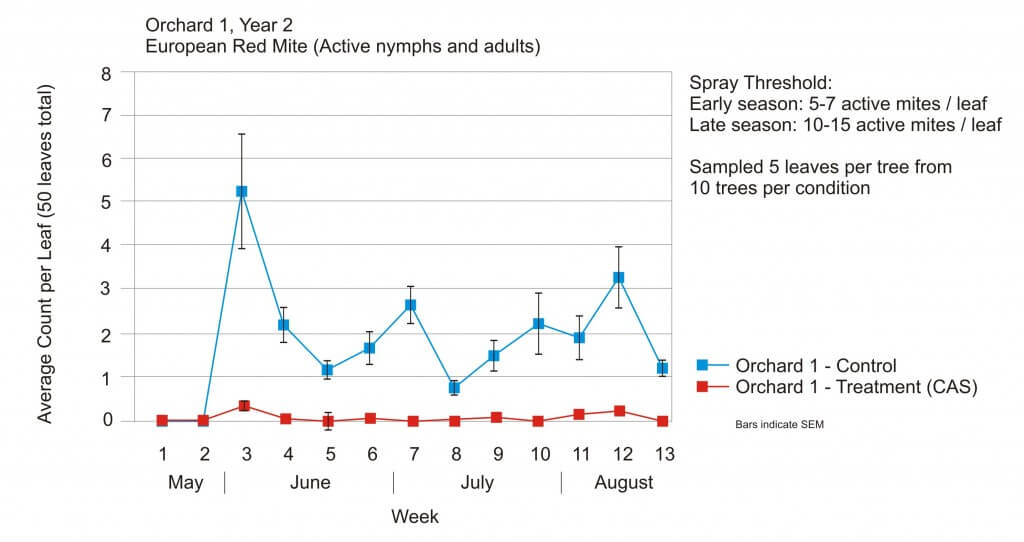

A scout was dispatched to monitor insect and disease activity each week for ~15 weeks. They observed a typical IPM scouting protocol and were not informed which block was the traditional control and which was CAS treatment. Data was transformed where appropriate for analysis of variance. In almost every case, there was no significant difference in counts between the CAS treatment and the grower’s traditionally-sprayed control (p=0.05). In those few cases where a pest had higher counts in the CAS block, the counts were so far below a spray threshold as to be insignificant.

If we look more closely at the three (of 128) ANOVA comparisons of control to treatment, we see that economic thresholds are rarely an issue, and essentially, difference between control and treatment are moot.

This study was repeated over three years. Having examined the data to determine if three years of optimized doses had any effect on pest populations, results suggest no such effect.

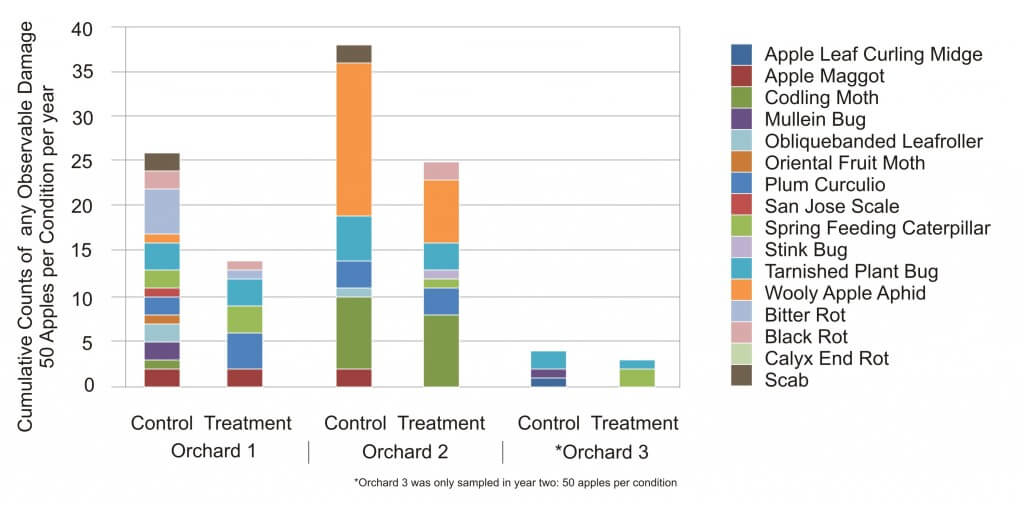

Apples were randomly sampled for destructive analysis at harvest and the total counts of any and all damage are shown below. This is simply a tally, and no statistical significance is implied. Note that Orchard 3 was only involved in the study for two years, and unfortunately a killing frost destroyed their harvest in their second year, so we didn’t have much to harvest.

An important part of knowledge transfer is whether or not growers will choose to adopt a method once the instructor is gone. By year two the biggest challenge was ensuring the orchardists in the study continued to spray the control block at their traditional volumes! They were more than willing to adopt the method wholesale and all three did so starting in 2016. Further, colleagues in Nova Scotia performed their own CAS trial for two years, and reported no significant difference in pest activity or apple quality. They accomplished this simply by following a written protocol.

The orchardist’s enthusiasm, the ability for the study to be replicated without my direct involvement, and the successful results speak to the viability of the method.

We would like to thank the researchers that developed the methods CAS is based upon, statistician Behrouz Eshani, the orchards that cooperated in the study, my OMAFRA colleagues and the OMAFRA summer students that scouted those orchards for three years.

More information

This method of application is really no more sophisticated than the pro rata practice of turning off nozzles that are aiming at the ground or above the target. It will take time for operators to get comfortable with the new volumes (and potentially reduced dosage) and regular scouting is highly encouraged to confirm they are achieving control.

The maintenance, calibration and operation of an airblast sprayer is an involved process. Collectively, the sprayer setup, weather and crop morphology all influence the coverage obtained from an application. A fundamental understanding of application technology is required before attempting to optimize dosage using the CAS method. We suggest grabbing a copy of the second edition of Airblast101 – Your Guide to Effective and Efficient Spraying. The digital version is a free download, but you can buy a hardcopy as well.

Finally, take a few minutes to watch this video by AAMS-Salvarani. In many European countries such as Belgium , France and Germany, sprayers must be calibrated regularly. While there is no mention of air speed adjustments, many of the steps in this video correspond with the airblast adjustments relating to Crop-Adapted Spraying.