Author’s note: Minor edits were made to this article on December 12, 2025. While the results remain unchanged, aspects of the interpretation have been adjusted upon reflection.

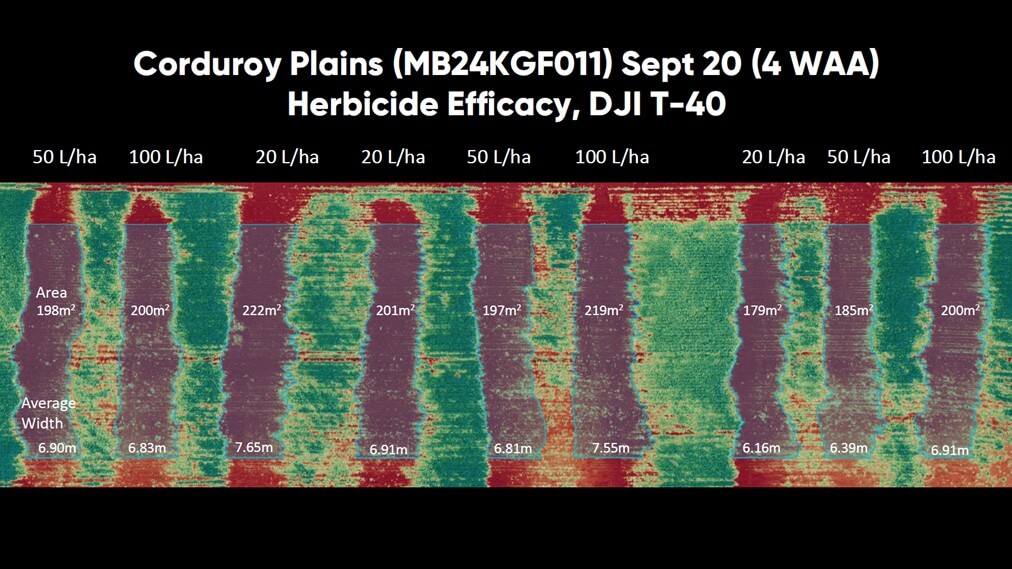

In 2024, Corteva conducted a study entitled “Drone-Delivered Herbicides: Comparing Lontrel XC (Clopyralid) Efficacy Across Application Techniques and Water Volumes”. Their objective was to compare the relative efficacy of hand booms and drones, and to determine if drone efficacy was affected by low water rates. The researchers evaluated the area treated and the effective swath width by manually tracing the burned areas from an aerial NDVI image.

Interestingly, the study found that water volume had an insignificant impact on herbicide efficacy. But what really caught our attention was the inconsistent and variable shape of the treated area along each flight path (Figure 1).

If the swath width fluctuates and vacillates along the flight path, then there is great potential for overlaps and misses throughout a treated area. Common practice is to rely on displacement (and drift) from upwind passes to deposit a sufficient cumulative dose of herbicide to mask areas of low coverage. This would be facilitated by consistent wind direction, higher altitudes, and a surface with little or no canopy to interfere with secondary deposition.

On the other hand, if the programmed swath width (i.e. route spacing) is too wide, and/or the the droplet size too large to permit sufficient displacement, then gaps in coverage would appear. And there is always the consideration of restricting the deposit to field boundaries and margins, particularly on the downwind side of the treatment area.

We explored these considerations by conducting a study that emulated aspects of Corteva’s work. We applied Roundup Transorb HC (a non-selective herbicide) instead of Lontrel (a selective herbicide specifically for broadleaf weeds). We used the DJI Agras T50 and the new T100 with two atomizers and a DJI RTK-2 base station, employing an array of operational settings. And, we flew multiple passes rather than a single pass for each treatment.

Part one of the study examined three programmed swath widths from both drones to compare their performances directly. Part two of the study evaluated the T100’s performance over a series of flight speeds and spray qualities. Burndown was evaluated using post-application orthomosaic images taken at 200 feet using a DJI M3M drone. Images were analyzed using Pix4D software.

Materials And Methods

Field Conditions

Applications took place in a 160-acre field of wheat stubble in Central Elgin, Ontario (42°45’29.3″N 81°05’58.9″W) on September 13, 2025.

Treatments

Each flight was centred on the right boundary of the treatment block, as indicated by a pin flag. Four passes were flown per treatment (i.e. two out-and-backs). There were no repetitions for treatments, so there was no need to randomize them.

Part One

The intent of this part of the study was to make a direct comparison of the swaths produced by the T50 and the T100. The T100 is heavier, has a larger volumetric capacity (100 L vs. 40 L) and is capable of faster flight (20 m/s or 64 km/h vs, 10 m/s or 23 km/h). We wrote about our first impressions of the T100, here.

Drone operational settings were selected to replicate those used in previous corn and wheat fungicide experiments with the T50. These settings are admittedly more restrictive (from the perspective of productivity) than those commonly used for herbicide applications. For example, and anecdotally, we have been told the T100 can spray a full section (~260 hectares or 640 acres) at 2.8 gpa and 20 m/s on one tank and one battery charge. However, we have no information about subsequent coverage, efficacy or off-target deposition.

Maintaining these operational settings allowed us to make a more direct comparison of herbicide vs. fungicide placement and efficacy. All applications were performed using a 250 µm spray quality (Table 1).

| Treatment Code | RPAS | Programmed Swath (m) | Speed (m/s, km/h) | Altitude (m) | Volume (gpa) |

| A | Unsprayed | – | – | – | – |

| B | T50 | 6 | 6, 21.6 | 3 | 5 |

| C | T50 | 8 | 6, 21.6 | 3 | 5 |

| D | T50 | 10 | 6, 21.6 | 3 | 5 |

| E | T50 | 6 | 10, 36 | 3 | 5 |

| F | T50 | 8 | 10, 36 | 3 | 5 |

| G | T50 | 10 | 8, 28.8* | 3 | 5 |

| H | T100 | 6 | 6, 21.6 | 3 | 5 |

| I | T100 | 8 | 6, 21.6 | 3 | 5 |

| J | T100 | 10 | 6, 21.6 | 3 | 5 |

| K | T100 | 6 | 10, 36 | 3 | 5 |

| L | T100 | 8 | 10, 36 | 3 | 5 |

| M | T100 | 10 | 10, 36* | 3 | 5 |

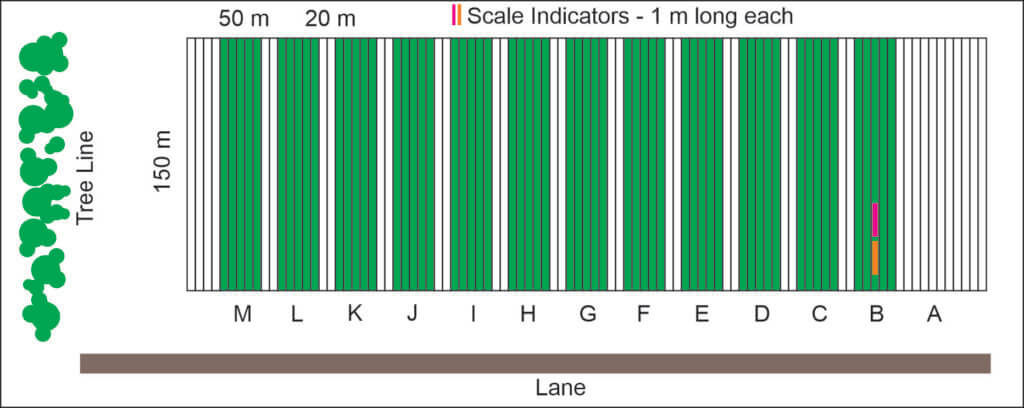

Each treatment block was 150 m long, 50 m wide and a 20 m buffer was maintained between treatments (Figure 2). Two, 1 m scale indicators were placed in Treatment B to confirm scale during image analysis.

Part Two

The intent of this part of the study was to explore the new drone design and its capabilities. Particularly, the impact of high-speed flight on swath width, displacement and drift. The DJI controller advises an altitude of 5 m or higher (likely a safety consideration). We felt this was too high for consistent coverage, and compromised by flying at 4 m (Table 2).

| Treatment Code | RPAS | Spray Quality (µm) | Speed (m/s, km/h) | Altitude (m) | Volume (gpa) |

| N | T100 | 500 | 18.3, 65.8† | 4 | 3 |

| O | T100 | 250 | 18.3, 65.8† | 4 | 3 |

| P | T100 | 80* | 12.5, 45* | 4 | 3 |

| Q | T100 | 250 | 18.3, 65.8† | 4 | 3 |

| R | T100 | 250 | 15, 54 | 4 | 3 |

| S | T100 | 250 | 10, 72 | 4 | 3 |

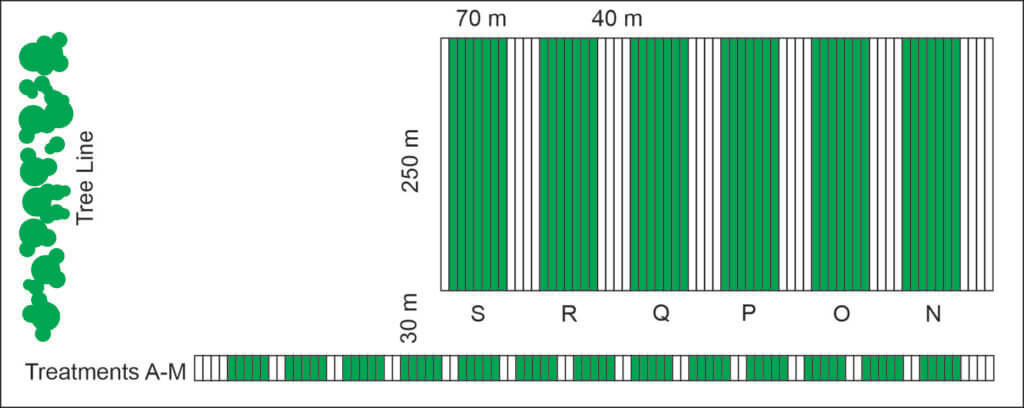

Given the greater potential for displacement and drift in this part of the study, we established wider and longer treatments blocks, and wider buffers between treatments. Each treatment was 250 m long, 70 m wide and a 40 m buffer was maintained between treatments (Figure 3).

Chemistry

The spray solution (PMRA research authorization 0054-RA-25) was premixed in a single batch. For part one, 80 L Roundup Transorb HC in 1,000 L water plus 0.05% Halt (defoamer). For part two, 700 L of the solution remained, so we added an additional 20 L of Roundup to approximately maintain the dose when dropping from 5 gpa to 3 gpa. This is a high dose of Roundup (~1.5 L/ac), selected to ensure that every drop that landed would create an obvious burn for easier analysis. It does, however, also mean that any reduced dose (i.e. striping) between passes would likely be masked. Drones were refilled after each treatment (to 40 L for T50 and to 65 L for T100) to negate any weight effect on the magnitude of the downwash.

Weather

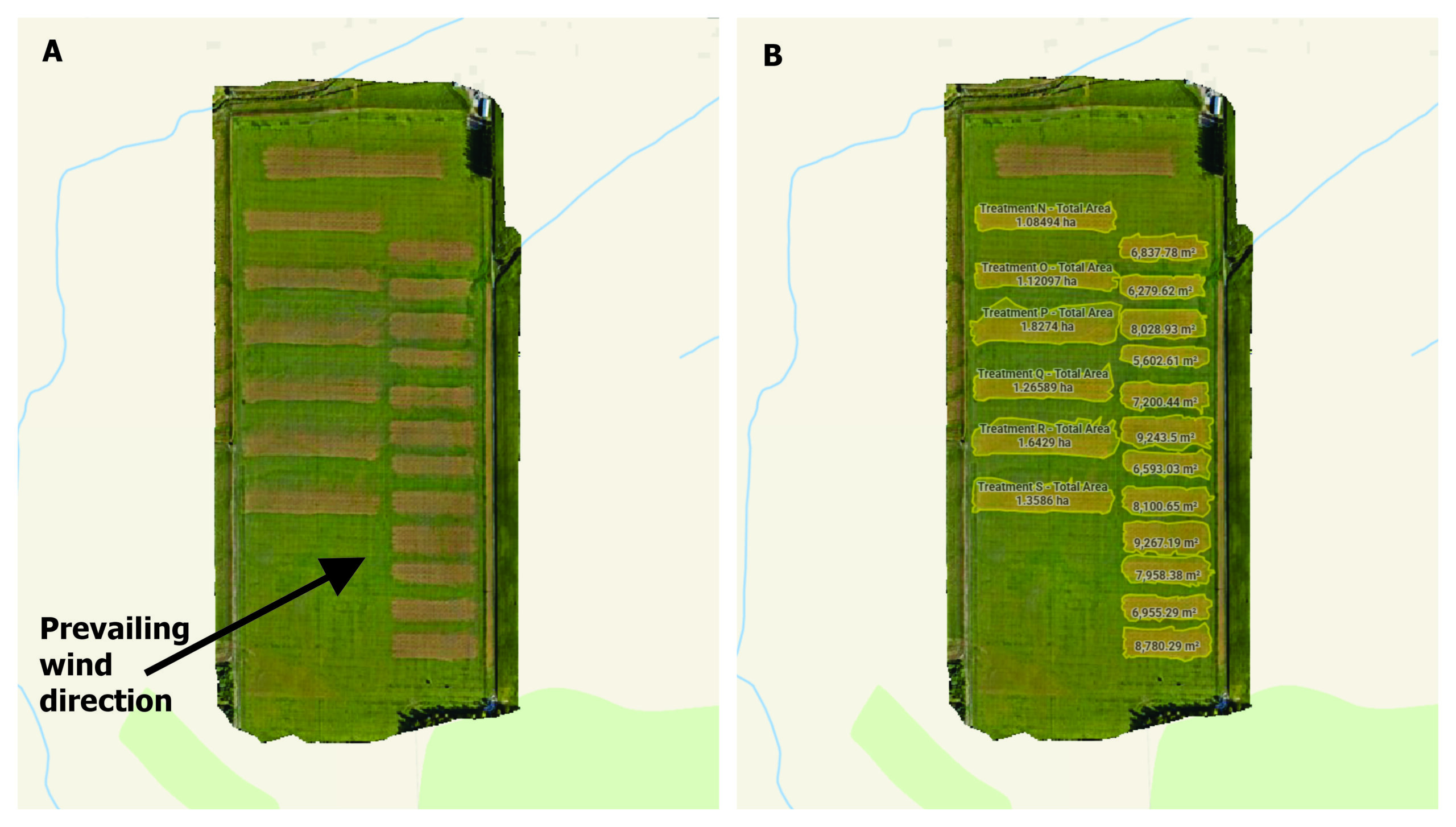

Weather data was collected using a Kestrel 3550AG weather meter (Kestrel Instruments) in a vane mount positioned 2.5 m above ground (Table 3). For part one, conditions were ideal: humid with a light wind in a consistent direction. For part two, afternoon wind speed increased, but predominant direction remained consistent (Figure 4A).

| Time | Experiment Part | Treatment | Weather |

| 10:05 – 10:58 | 1 | B – G | 18.6 ̊C, 78% RH, 0.0 km/h wind. |

| 10:58 – 12:40 | 1 | H – M | 19.8 ̊C, 72% RH, 2.0 km/h wind. |

| 12:40 – 1:50 | 2 | N – S | 22 ̊C, 61.2% RH, 7.0 km/h wind. |

Estimating Effective Swath Width

The burned area meets or exceeds an efficacious dose, which is a variable that can only be assumed using traditional sampling systems. Traditional methods for calculating effective swath width (ESW) utilize a sampling system aligned perpendicular to the flight path. Whether dyes or water sensitive paper, this approach produces a coefficient of variation and some measure of over- and under-dose based on a target threshold (dose or coverage). The two methods used in this study are subjective, and there are inherent flaws, but they still provide valuable information. A more realistic representation of ESW likely falls between the two.

In the first method, the perimeter of the area burned was traced to create a polygon (above, in Figure 4B). Then, the average width of that area was established from measured spans along the block. Finally, that average was divided by the four passes. Hereafter referred to as the “treatment width ÷ passes” method. This method produces an underestimate of ESW because each upwind drone pass can overlap and hide any displacement (and drift) from the previous. It divides the drift over however many passes are made.

The second method overlays the flight path onto the area burned. The upwind side of the swath was determined from an average of at least five measurements along the upwind flight path. The downwind side of the swath was calculated the same way (Figure 5). Both the average upwind and downwind distances were added to arrive at the ESW. Hereafter referred to as the “port + starboard extent” method. This approach captures a clear representation of the upwind side of a single pass, but overestimates ESW by including any cumulative increase in drift from multiple passes on the downwind side.

Results – Part One

Planned versus Measured Treatment Area

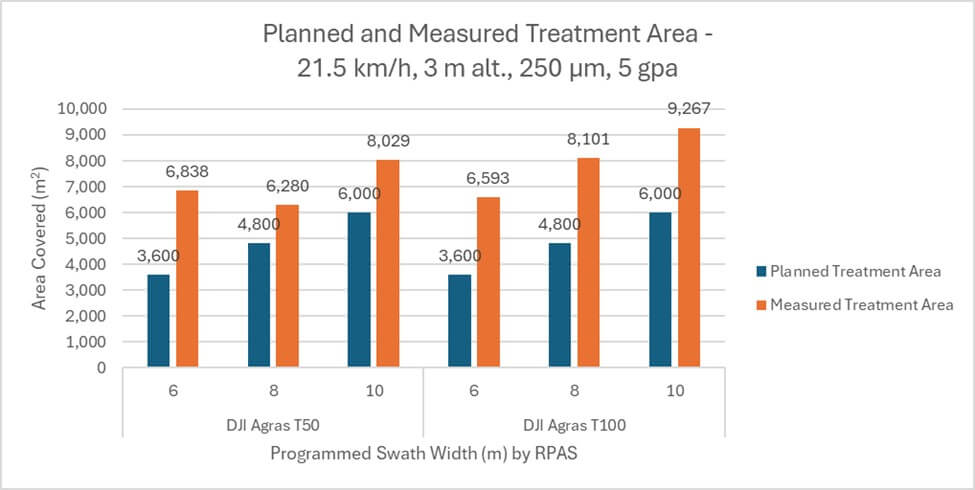

Planned treatment areas were calculated from distance flown × programmed swath width × number of passes. Measured treatment areas were calculated by tracing a polygon along the perimeter of the area burned. In all cases, actual was larger than planned by an average 36.1%. The T50 treated 32% more area than planned and the T100 treated 40% more area than planned, or 8% more than the T50 (Figure 6).

Programmed and Measured Swath Widths

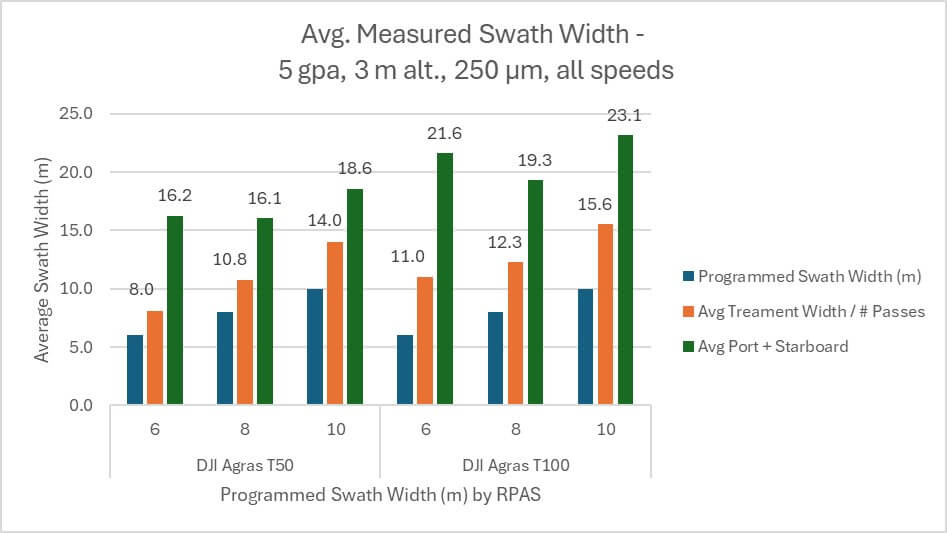

In all cases, the “treatment width ÷ passes” method produced a swath width that was greater than, and positively correlated with, programmed swath width (Figure 7). For the T50, it was an average 26.8% wider. For the T100, it was an average 38.3% wider. The swath widths calculated by the “port + starboard extent” method were larger still, but were not positively correlated with programmed swath width. For the T50, it was an average 52.8% wider. For the T100, it was an average 62.5% wider.

No matter the method used to calculate swath width, the T100 exceeded the planned swath width by more than the T50. Using the “port + starboard extent” method, the average T100 swath width was 21.3 m, which is an average 15.4% wider than the average 17 m swath produced by the T50.

T50 Swath Width by Travel Speed

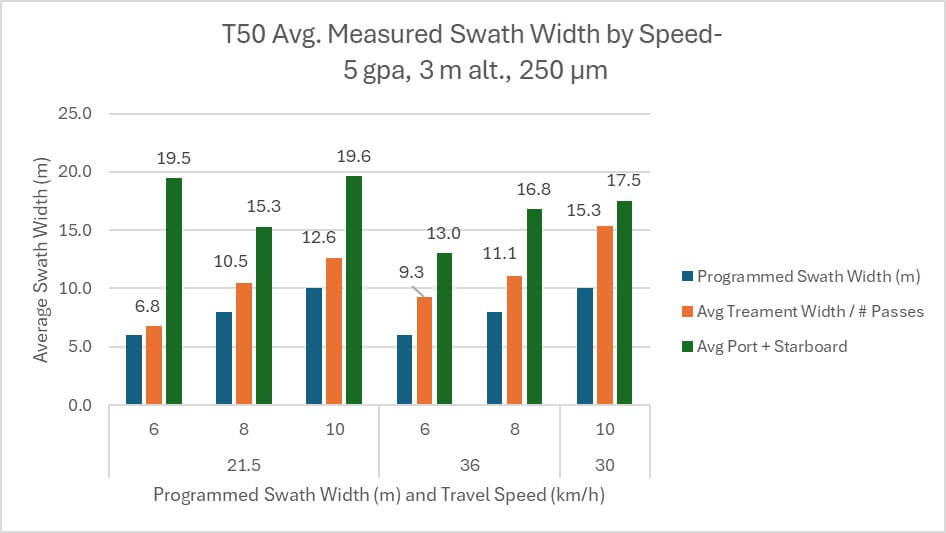

When travel speed becomes the independent variable for the T50, the “treatment width ÷ passes” method produces average swath widths that positively correlate with flight speed. At 21.5 km/h, the average swath was 10 m, increasing to 11.9 at 30-36 km/h (Figure 8). This is typical and expected as higher speeds have been shown to produce wider swaths with the T10 and T50.

However, the relationship between speed and swath width is less clear when calculated using the “port + starboard extent” method. At 21.5 km/h the average swath was 18.2 m, but reduced to 15.8 km/h at 30-36 km/h (Figure 8).

T100 Swath Width by Travel Speed

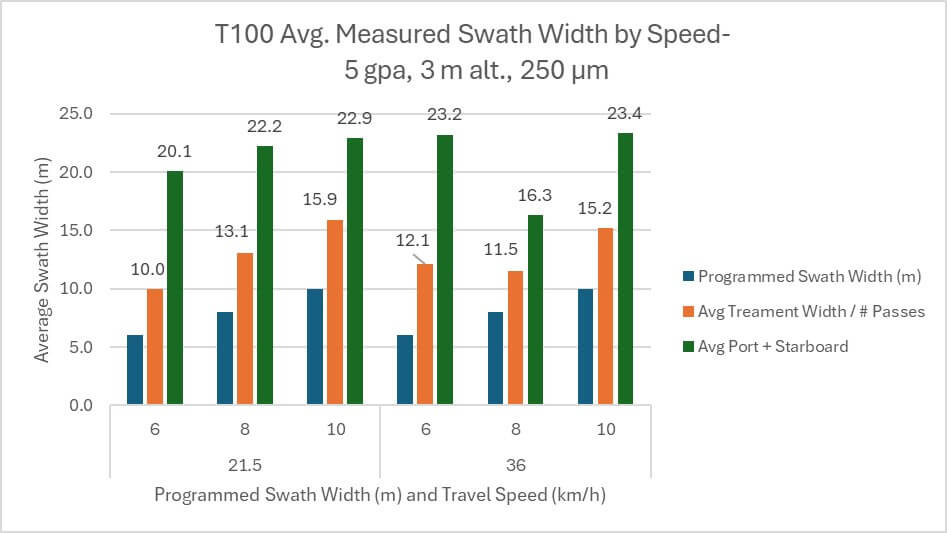

When travel speed becomes the independent variable for the T100, neither method for calculating swath width show an effect from flight speed. The “treatment width ÷ passes” method produced average swath widths of 13 m at 21.5 km/h and 12.9 at 30-36 km/h (Figure 9). The “port + starboard extent” method produced average swath widths of 21.7 m at 21.5 km/h and 21 at 30-36 km/h.

Results – Part Two

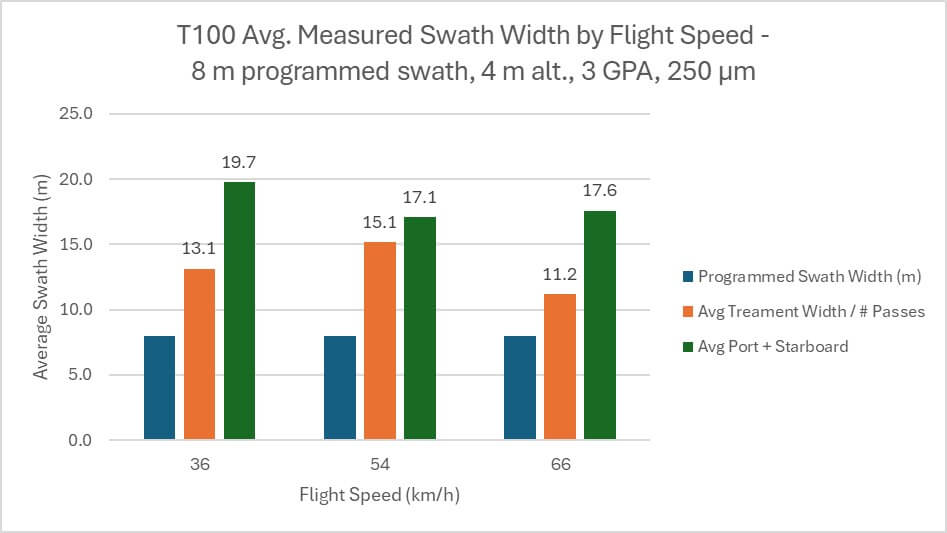

T100 Swath Width by Travel Speed

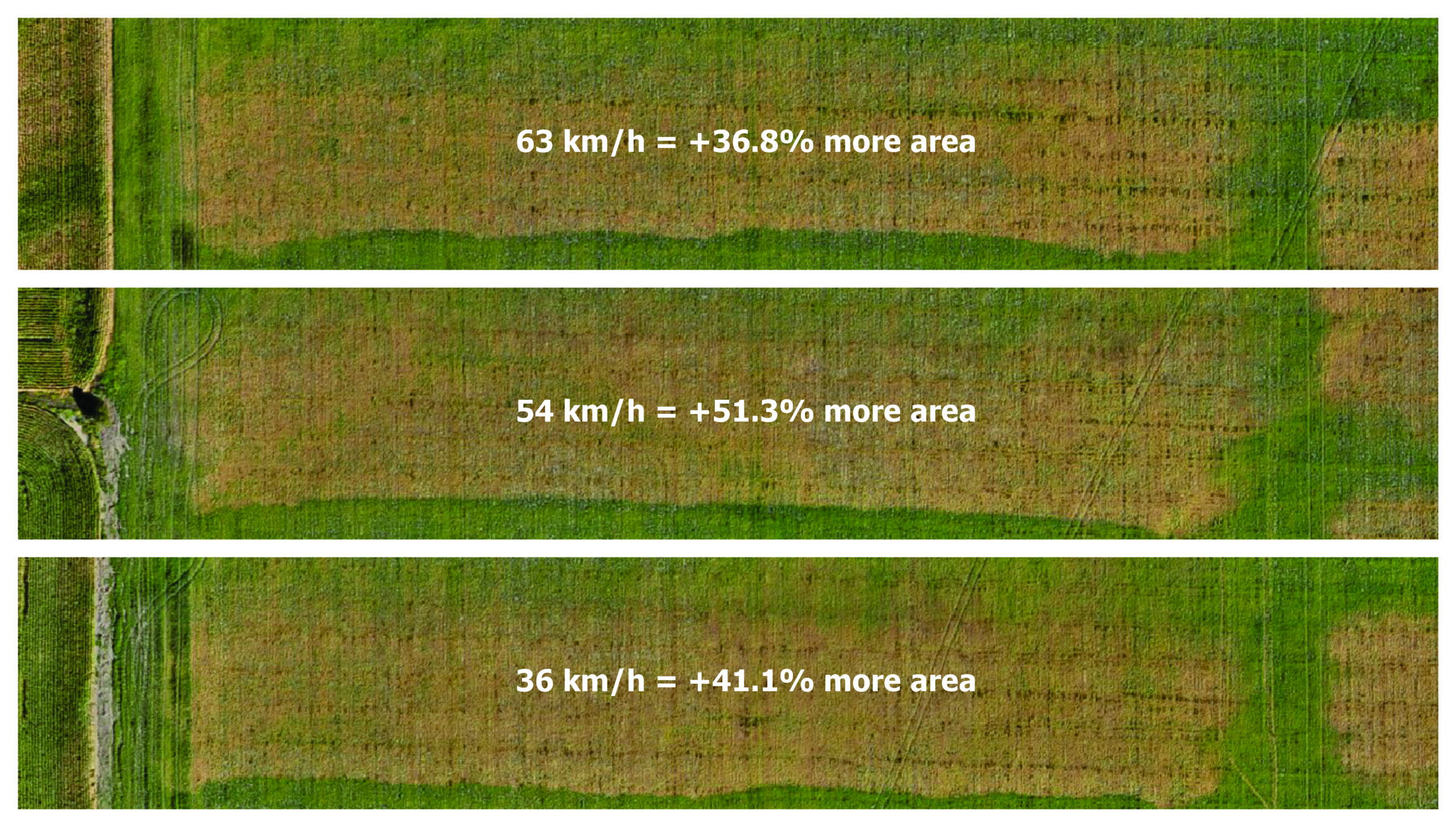

The effect of flight speed on treated area and swath width was examined. In each case, the treated area was significantly larger than the programmed area (Figure 10).

Similar to Part one, travel speed did not appear to influence swath width in any consistent or significant way (Figure 11).

T100 Swath Width by Spray Quality

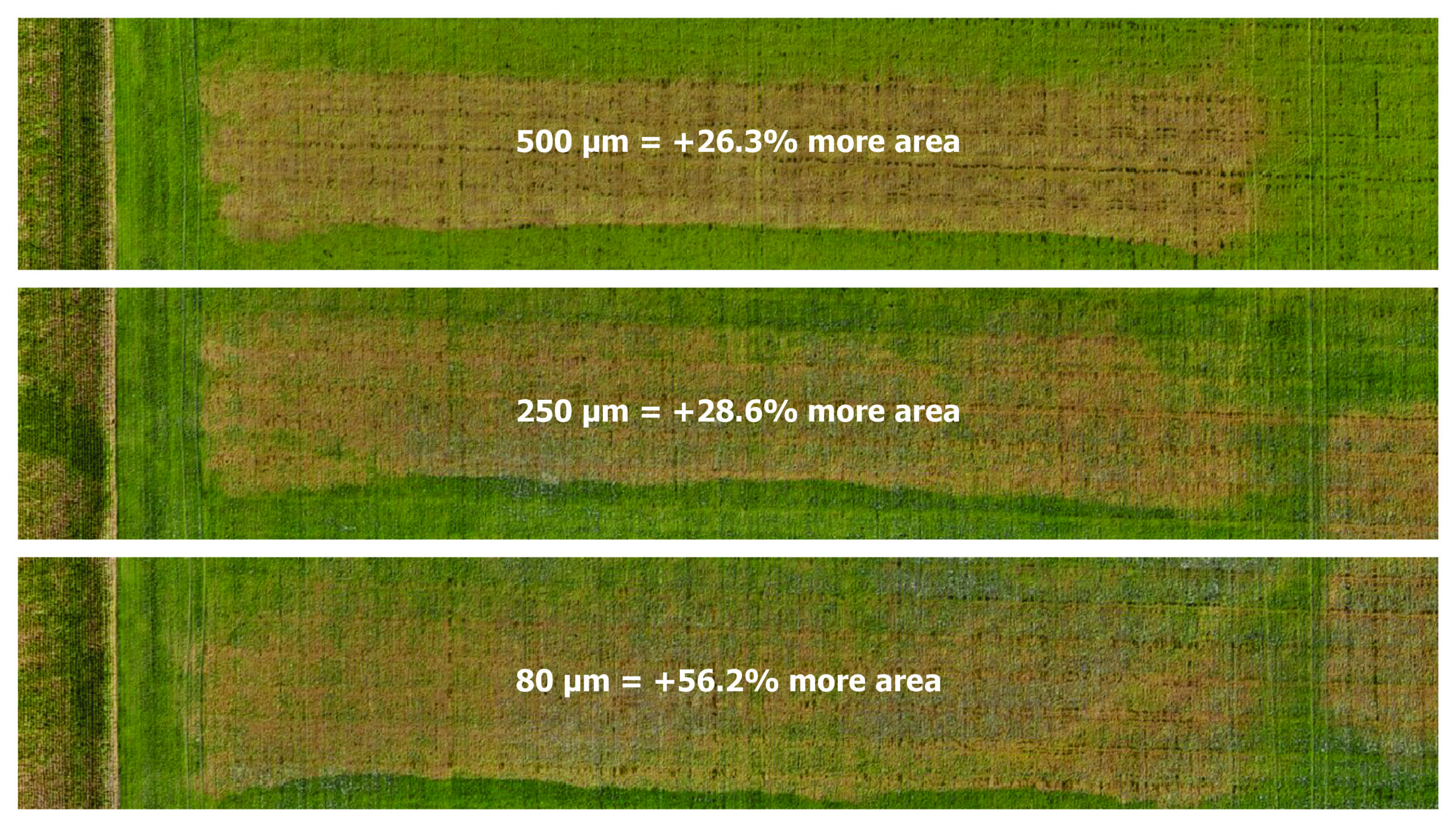

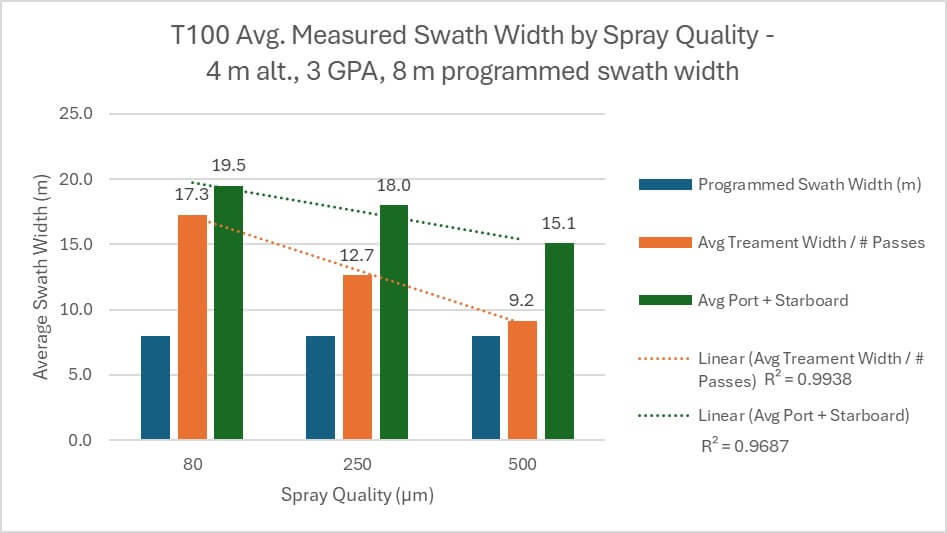

The effect of spray quality on treated area and swath width was examined. Once again, in each case, the treated area was significantly larger than the programmed area (Figure 12).

Swath widths from both calculation methods were negatively correlated with spray quality (Figure 13). Coarser droplets have greater mass, making them are less prone to displacement by wind than finer droplets. The “treatment width ÷ passes” saw an 80 μm spray quality produce a swath 46.8% larger than a 500 μm spray quality. The “port + starboard extent” method saw an 80 μm spray quality produce a swath 22.6% larger than a 500 μm spray quality.

Discussion

In all cases, the area treated (i.e. burned) exceeded the area planned. The T50 covered 32% more area while the T100 (using the same operational settings in the same environmental conditions) covered 40% more. This implies that the T100 created wider swaths and/or drifted more than the T50.

The swath widths calculated from herbicide efficacy appear to be considerably larger than those observed in previous studies that focused on coverage and fungicide efficacy. This is likely a function of herbicides having a lower threshold dose, and their application on bare earth or into sparse canopies permitting the lateral spread of droplets. When even the slightest degree of coverage produces a visual effect, this binary result (hit or miss) will certainly extend the effective swath width. This should raise awareness of the importance of field boundaries and margins, particularly with herbicides.

When estimating ESW, the method used affected the results. The “port + starboard extent” method resulted in large and low-resolution estimations of ESW, whereas the “treatment width ÷ passes” method seemed to respond in a more predictable way, even if it underestimates the ESW. Ultimately, both methods produce rough estimates; they are not intended to replace traditional, quantifiable assessment methods. The “truth” is likely somewhere in between.

With that caveat firmly in place, we assessed ESW using the “treatment width ÷ passes”. It was positively correlated with flight speed for the T50, as observed in previous work. However, this was not the case with the T100. Given that both drones were operated using the same settings, it is unclear why the T100 would produce such erratic results. Future work will evaluate T100 ESW using conventional methods.

When the T100 was flown using a span of three droplet sizes, there was a strong negative correlation between average droplet size and ESW. Once again, this aligned with previous experience. While rotary atomizers on drones tend to create smaller droplet sizes than reported by the flight controller, coarser droplets have greater mass, making them less prone to displacement by wind.

However, when the T100 was flown at at three speeds, the relationship with ESW was once again unclear. When flown at 36 km/h (~10 m/s) the T100 was flying at the top speed of the T50. It also flew at 54 km/h and at 66 km/h, which was the highest speed we could achieve at 5 gpa. The ESW (as estimated using the “treatment width ÷ passes” method) was essentially unchanged. While it is possible (and likely) that any increase in effective swath width due to travel speed was obscured by drift, pervious work has shown that drift increases concomitantly with speed. That does not appear to have happened here.

Perhaps this is a function of a greatly reduced dwell time diminishing the effect of the downwash. Or, perhaps, the T100’s capacity for higher speeds has allowed it to pass beyond translational lift into true forward flight, similar to a helicopter. Translational lift occurs any time there is relative airflow over the rotor disk. As headwind and/or forward speed increase, translational lift increases, resulting in less power required to hover. According to Transport Canada, it is present with any horizontal flow of air across the rotor but most noticeable when the airspeed reaches 16 to 24 knots flight (8.25 to 12.8 m/s or 30 km/h to 46 km/h). This would greatly reduce the effect of the downwash on droplet movement. In our first impressions of the T100, we found that flying slower overheated the battery. This did not occur at higher speeds, and this efficiency supports the premise that it moved past translational lift, perhaps achieving true forward flight.

If this theory is correct, it’s a new development for rotary drones, which were not previously capable of reaching these speeds. Downwash was an unavoidable side effect of the flight, but may now be a tool for the operator to use as the situation warrants – battery temperature notwithstanding. Perhaps it warrants a return to horizontal booms positioned beyond the downwash in order to improve coverage uniformity. On the other hand, we saw that it took the T100 roughly 100 m to reach the target 66 km/h, meaning it moved from hover to translational flight and beyond over that distance. This raises questions about how they spray would respond throughout that transition.

More work is required.

Acknowledgements

Adrian Rivard and Stuart Hunter (Drone Spray Canada), Adam Pfeffer (Bayer Canada) and Mike Cowbrough (Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness) are gratefully acknowledged for their participation, and both in kind and financial support of this study. Thanks also to Mark Ledebuhr and Tom Wolf for discussions surrounding the interpretation of these results.