In the spring of 2016, the Ontario Berry Growers Association (OBGA) conducted a survey of its membership to poll how fungicides were being applied. The results were very interesting.

Fungicide basics

Generally, fungicides registered for berry crops are contact products, so coverage and timing are very important. The fungicide has to be distributed evenly on the target before disease has a chance to infect the crop. That means the sprayer operator must be aware of the susceptibility of the crop to the level of disease pressure to ensure timing is appropriate. While kickback and post-application distribution of pesticide residue is sometimes possible, sprayer operators should not rely on it. The following table outlines application recommendations for a fungicide commonly used in Ontario. It combines labelled information and provincial recommendations and is representative of most fungicides.

| Summer-fruiting and Fall-bearing Raspberry / Blackberry | Highbush Blueberry | Day-neutral and June-bearing Strawberry | |

| Labelled rate | 2.5 kg/ha | 2.25 kg in 1,000 L/ha | 2.75-4.25 kg in 1,000 L/ha |

| Diseases (Labelled and Ontario provincial recommendations) | Anthracnose fruit rot, Spur blight, Leaf spot, Botrytis grey mould | Anthracnose fruit rot, Shoot blight (Mummy berry), Botrytis twig and/or blossom blight | Common leaf spot, Botrytis grey mold |

| Crop staging | Bloom, Pre-harvest, Harvest | First bloom, Fruit ripening | Flower bud, First bloom, 7-10 days after bloom, Pre-harvest, Through to fall |

The spray target

The applicator reading the recommendations should be considering the best way to get the fungicide to the target. But, what is the target, and what is the best way to apply it? It seems the recommendations raise as many questions as they answer:

- With the possible exception of blueberry, this fungicide can be applied through much of the growing season (especially when it’s been a wet season). That means the crop staging is highly variable.

- The primary target is blossoms, but depending on the disease, leaves and stems are also important.

- The label states a volume of carrier (i.e. 1,000 L/ha) for strawberry and blueberry, but not the cane fruit. It does not specify highbush blueberry versus the sessile, ground cover variety.

So, this means is the sprayer operator has to spray crops with highly variable physiology (e.g. bush, cane or sessile row crops), onto very different targets (e.g. leaves, canes, stems, flowers) throughout much of the season as the crop canopies grow and fill. This is a very challenging spray application. It would be wrong to suggest a single spray quality, water volume or sprayer set-up to efficiently accomplish all these goals (more on that later). The first consideration is the application equipment itself.

The application equipment

Berry growers employ a variety of sprayers to protect berries. Without considering models or optional features, there are three fundamentally different styles: Airblast, backpack and boom. According to the survey, the following table shows which sprayers are used in which berry crop in Ontario. Approximately 60 growers responded, and many grow more than one variety of berry and use more than one style of sprayer.

| Airblast Sprayer | Backpack or Wand Sprayer | Vert. or Hor. Boom Sprayer | Total | |

| Highbush blueberry | 8 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Day-neutral Strawberry | 3 | 0 | 21 | 24 |

| June-bearing Strawberry | 5 | 0 | 32 | 37 |

| Raspberries & Blackberries | 21 | 1 | 7 | 29 |

| Total | 37 | 2 | 60 |

So, generally, cane and bush berries are sprayed using airblast sprayers and strawberries using horizontal booms. The survey didn’t specify features such as air-assist on booms, or whether or not those booms are trailed or self-propelled. The type of, and features on, any given sprayer dictate the limits of what an operator can adjust to improve coverage.

Water volume

Respondents also reported on how much carrier (i.e. water) they used to spray fungicide on their crops. Given Canada’s propensity to report volumes in many different forms, I have converted all values into the most common units: L/ha, US g/ac and the dreaded L/ac:

| n | L/ha ± std (max./min.) | US g/ac ± std (max./min.) | L/ac ± std (max./min.) | |

| Highbush Blueberries | 7 | 534.2 ± 340.1 (1,000/150) | 57.1 ± 36.4 (106.9/16) | 216.2 ± 138 (404.7/60.7) |

| Day-neutral Strawberries | 22 | 418.5 ± 192.2 (1,000/224.5) | 44.7 ± 20.6 (106.9/24) | 169.4 ± 77.8 (404.7/90.8) |

| June-bearing Strawberries | 33 | 403.1 ± 235.1 (1,000/50) | 43.1 ± 25.1 (106.9/5.3) | 163.1 ± 95.1 (404.7/20.2) |

| Raspberries & Blackberries | 27 | 450.1 ± 279.4 (1,200/50) | 48.1 ± 29.9 (128.3/5.3) | 182.1 ± 113.1 (485.6/20.2) |

There appears to be a lot of variability in the volumes applied, but on the whole, very few are using the 1,000 l/ha indicated in the fungicide recommendations. The ~430 l/ha overall average is no surprise; labelled volumes are quite often higher than what sprayer operators use. In some cases, high label volumes are warranted because the product requires a “drench” application to totally saturate the target, or to penetrate very dense canopies. Conversely, a high label volume might reflect outdated practices if that label hasn’t kept up with current cropping methods or application technology. Sometimes label volumes are suspiciously large, round numbers that suggest they are intended to encompass a worst-case scenario (e.g. a large, unmanaged crop with high disease pressure and a less-than-accurate spray application). In the particular case of crops sprayed with an airblast sprayer, it is very difficult for a label to accurately predict an appropriate volume due to the variability in crop size, density and plant spacing. This has led to methods to interpret labels, such as crop-adapted spraying.

The disparity between label language and grower practices is not entirely the fault of the label. Most sprayer operators don’t want to carry a lot of water because more refills prolong the spray day. In situations where the crop has reached a critical disease threshold, or bad weather has compressed the spray window, sprayer operators sometimes reduce the volumes in the belief that “getting something on” trumps “good coverage”. Perhaps that’s true, but insufficient volumes greatly reduce coverage. This can be further exacerbated when operators do not account for the increase in crop size and density over the season, or the impact of hot dry weather on droplet evaporation.

Improving coverage

So, is there an ideal sprayer set up and volume? As previously alluded, the variability in crop staging, crop morphology, target location and spray equipment make a single recommendation impossible. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t diagnostic tools and a few simple rules to help a sprayer operator determine a volume to suit their particular needs. Much can be accomplished with these three things:

- Water-sensitive paper

- A modest selection of nozzles and a nozzle catalogue

- An open-minded sprayer operator willing to spend a little time and reconsider traditional practices

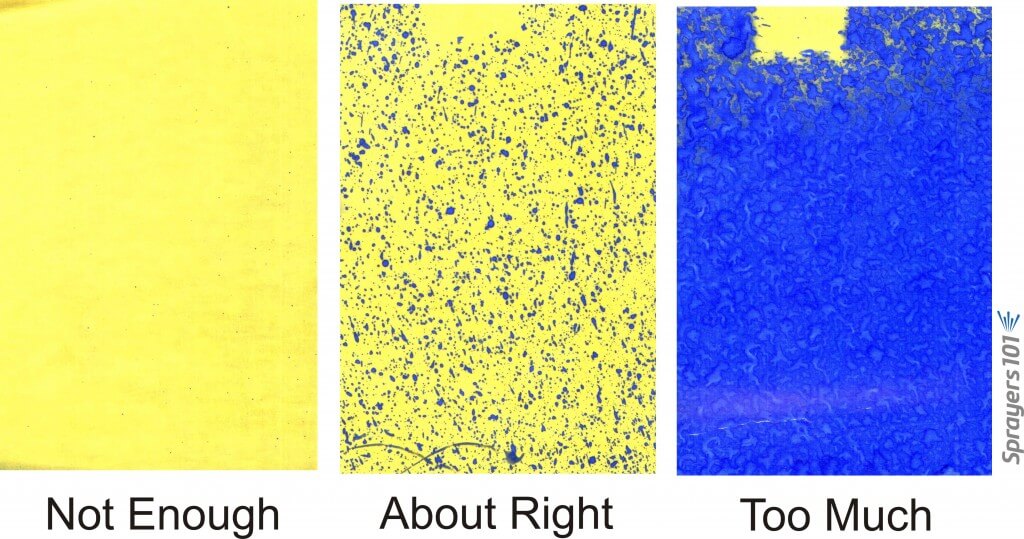

Water-sensitive paper is placed in the canopy, oriented to represent the target (e.g. leaf, bloom, etc.). It is important to put multiple papers in at least three plants to ensure the coverage reflects a typical application. The paper changes colour when it’s sprayed and this provides valuable and immediate feedback. Did the spray go where it was supposed to go and did it distribute throughout the target? If so, then the operator now knows that they can safely focus on timing rather than targeting. If not, a little diagnosis is required:

1. Were targets completely drenched? If so, there is too much coverage. Operators can drive faster (if possible, and as long as it doesn’t create drift), reduce operating pressure (if possible, and as long as the nozzle is still operating in the middle of its registered range), or change nozzles to lower rates (as long as spray quality is constant).

2 .Were targets only partially covered, as if a leaf obstructed part of the target and created a shadow? This mutual-shading is the bane of spraying dense canopies. One possible solution lies in understanding droplet behaviour: Coarser sprays generally mean fewer droplets and they move in straight lines. Therefore, when they hit a target, they might splatter or run-off, but typically their journey is over. If the spray is too Coarse, a slightly Finer spray quality increases droplet counts and may help droplets navigate around obstacles and adhere to more surfaces. Sprays that are too Fine will not penetrate dense canopies without some form of air assist. They slow very quickly and tend to drift and evaporate before they get deep enough into a canopy to do any good. A Medium droplet size is a good compromise because it produces some Fines and some Coarser drops – the best of both worlds.

Increasing volumes and reconsidering spray quality often helps, but there might be other options. If using air assist, there are tests that can confirm the air volume and direction are appropriate. Another solution might lie in canopy management (where pruning bushes and canes can help spray penetration immensely). Still another might lie in the use of adjuvants to improve droplet spread on the target.

3. Were targets missed entirely, or coverage is consistent but sparse? The operator is likely not using enough water, and/or the spray quality is too fine. It has been demonstrated time and again that higher volumes improve coverage, but operators can try any of the options listed previously for partially-obstructed coverage. All the reasoning is the same.

Spraying fungicides effectively requires an attentive sprayer operator. Timing and product choice are very important, but when it is time to spray the sprayer operator should diagnose coverage with water-sensitive paper, and be willing to make changes to the sprayer set-up to reflect changing conditions. Thanks to the OBGA for sharing the survey data.